Hardness is best defined as a property possessed by a substance to resist abrasion when a pointed fragment of another substance is drawn across it.

Hardness is related to the atomic bonding of a substance i.e. loose bonding between atoms generally gives rise to lower hardness and vice-versa e.g. diamond and graphite, the two polymorphs of carbon, have a hardness of 10 and 2 respectively.

Mohs’ Scale: This is a universally used scale of hardness devised by a German Mineralogist Friedrich Mohs (1773-1839). This scale is based on the principle that a harder mineral will scratch a softer mineral. To serve as a standard of comparison, Mohs selected ten well-known and easily obtainable minerals. The ten standard minerals used in Mohs’ scale, in their increasing order of hardness are given in the box. Two important factors to be remembered are:

- Mohs’ scale is not a linear scale but a relative one (i.e. the difference in absolute hardness between corundum at 9 and diamond at 10, is much greater than the difference between corundum at 9 and topaz at 8).

- The ten chosen minerals are those which are easily available and exhibit a fairly constant hardness from specimen to specimen.

Hardness of:

- Fingernail is about 2.5.

- Window glass is about 5.5.

- Steel file about 6.5.

- Copper coin is about 3.

- Knife blade is about 6.

Directional Hardness

Some crystalline gem materials show distinct difference in hardness along different directions.

- In kyanite the difference is very pronounced; it has a hardness of 4 along the longer dimension and 7 at right angles to this i.e. the same large face of kyanite gives different values for hardness depending upon the direction of scratching.

- In case of diamond the dodecahedral face is the softest, and the octahedral face is the hardest.

- The angles and edges of a crystal are sometimes harder than the faces of the same mineral, e.g. the edges of a topaz crystal will scratch the face of another topaz crystal. Hence gem stones having a similar hardness can scratch each other.

Procedure for Hardness testing: Two (2) common methods used for scratch hardness test are:

- Hardness Pencils: In this, pointed fragments of standard minerals on Mohs’ scale (4 to 10) are mounted on metal or wooden holders. The hardness point should be applied firmly to some inconspicuous part of the specimen to be tested. Always start with the softer pencil and proceed up the scale until just a visible scratch is seen. Examine the scratch with a 10x lens to ensure that it is a scratch and not powder from the point itself.

- Hardness Plates: This is a safer method for testing scratch hardness since the plate is scratched by the edge (girdle) of the specimen. You can use polished plates of quartz, topaz, synthetic corundum and diamond. They need not be of gem quality. A polished plate of synthetic corundum can be used for testing of diamond since diamond is the only natural substance which can scratch corundum. A man-made material which can scratch corundum is silicon carbide (synthetic moissanite).

Precautions:

- If it is really necessary to apply the hardness point or file on faceted stones, never scratch the table or culet.

- If the stone is not mounted then work on the girdle, if not then try to work as near to the girdle as possible.

- It is better to let the specimen to be tested act as a hardness point against polished plates of standard hardness.

Limitations:

- A hardness test is a destructive method of identification hence it should be used as the last resort.

- If too much pressure is applied while testing a brittle stone like an emerald it is liable to break.

- A hardness test cannot distinguish between natural and synthetic stones because they have the same hardness.

- Paste jewellery and lesser known valuable gemstones can be damaged by this test.

- Along a cleavage direction, a stone is liable to split into two.

- A hardness test should be used in a limited manner. There are more accurate methods which can be employed in gem identification.

Importance of Hardness to a Gemologist and a Lapidary:

- The hardness of a gem affects the appearance of the stone in terms of surface luster and polish. This helps the gemologist to get an idea about its identity. Harder the gemstone, higher the lustre e.g. Apatite has a duller lustre than beryl.

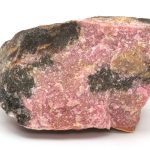

- For unknown rough, the hardness test plays an important role. A Hardness pencil of known hardness used on unknown gemstones can help to make a rough identification.

- Harder gemstones generally take a better polish than softer ones. Since a lapidary knows what plate should be used for polishing, he can distinguish one stone from another by knowing the hardness, e.g. a diamond from topaz or quartz.

- Directional hardness plays an important role. This is of use to the gemologist in separating blue kyanite from blue sapphire. It is useful to the lapidary in identification as well as in deciding the direction for faceting and polishing a stone.

- Knowledge of hardness enables a lapidary to control the speed of cutting and the quality of the polishing powder to be used. While mounting a gemstone in jewellery, it may have to endure the occasional hard knock or abrasion. Knowledge of hardness would help reduce damages during the setting stage also.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.